Join Hempstead High School teachers Jean Loup Hogu and Danielle Golub and Herstory workshop facilitator Helen Dorado Alessi as they share their life-changing experiences using Brave Journeys in their ENL classrooms.

Author: eduncan

Josue by Helen Dorado Alessi

What do you think it feels like to be a 15-year-old boy from Honduras newly arrived to a Long Island high school? Can you imagine being this boy who is painfully shy and small for his age? Close your eyes and imagine that you are this boy. You have deep brown eyes that hardly ever look directly at anyone, but down to the floor or on your desk when you speak. And when you speak, your voice is so quiet that we barely hear you. You’ve been here for only six months but it feels like a lifetime. Your face reveals so little but I know that there is deep emotion there.

The classroom is large and the desks and chairs are already in a circle. On the walls are educational decorations, vocabulary lists, homework assignments, and testing schedules. It’s very warm and I can hear the kids on the soccer field right outside the window. All 10 students have been working for weeks on their stories. Each week the stories evolve as the writers push themselves to go deeply back into memory and give voice to a never-spoken personal story.

There is one student that I am most worried about in this class. His name is Josue. Will he be able to open up and share what his journey to the United States from Honduras was like? Without being overly dramatic, I feel his life may depend on it. I never know what will come out when the quiet ones share and how painful it might be, but I am ready and I think he is, too.

It’s been weeks, but I do not know Josue’s story at all. He’s never read it out loud. He doesn’t trust me or maybe anyone, not even himself. There’s a lot of effort that goes into trying to forget and keeping the memory of tough experiences buried. I know he is writing. I see the words on the paper but he is super protective of what is on that page. Each time I walk past his desk, he covers the paper with his arm and puts his head down on top of it. I really feel that I must be gentle but sure with him. This is the last day of class. If he does not read, he will see this as another failed experience. No regrets here, Josue. Just do your best and so will I.

The students prepare to volunteer to read. This time is usually a bit of a waiting game for me. “Be patient, Helen,” I tell myself. They fidget as they look from one to the other to see who wants to read first. This is taking some time. Or does it just feel like that because I am impatient to hear Josue’s story? We go around the circle listening to the wonderful and haunting stories that emerge from your classmates. I begin to wonder, How will you feel about yourself when they read in English and you can’t?

I remind the class that all are to feel free to read in English or Spanish. “Whatever makes you most comfortable.” There’s enough courage needed in exposing their stories without having to worry about pronunciation and so forth. “We can translate the stories into English together later on,” I tell them.

As we go around the circle, we reach you. So, it’s now your turn to read. I am nervous for you, Josue. And you must be, too, because you say in a low voice, “No, no quiero” — No, I don’t want to. “Okay, Josue, sin problema,” I tell you. “We will come back to you.” There are four students left to read and after each one of them I return to you to give you a chance to read.

Andrea? Andrea reads her piece about her family celebrating the New Year in Honduras. She describes the custom of carrying the family’s favorite piece of luggage around the outside of her house to illustrate another year’s passing. She tells it with such heart. It is really beautiful and makes me think, Did she use that same Maleta for her journey to the United States? The whole family is part of this yearly ritual; they laugh and sing as abuelos, tias and primos all hold hands thanking God for the past year and praying for a good new year. As she finishes her story the students seem lost in their own memories of family customs of their own towns in Central and South America.

I ask Josue to read, but I am not surprised that he’s not ready. I call on the next student. Luis, Estas listo? Luis straightens up in his chair, fidgets with his papers. He shares his piece on life in El Salvador:

“My name is Luis. I had to leave my country or I was going to be killed . . . The gang was after me to join . . . They wanted me to sell drugs and they chased me in school, never letting up . . . Never leaving me alone. . .

“I was so scared and my mother feared for my life . . .

“It was a nightmare that I could not wake up from no matter how hard I tried . . . The teachers knew what was happening . . . It was happening all over the school . . .

“I stopped going to school but they hunted me and one day when I got back from the store they were waiting for me in my living room . . . They were angry and nervous . . . They knocked things down and broke my mom’s little cat figurines and some plates . . .

“The biggest one took out a gun and put it next to my head . . . You join or die right now . . . That’s when I knew, I knew I had to run, run far away.”

Luis’ voice trails off. He is no longer in the classroom on Long Island, NY. His mind is back there, in that moment of desperation.

There is silence. I look around the room at the other students’ faces. They are engrossed in Luis’ story. He has done a very good job of helping us feel the drama of the scene. I tell him exactly that. I do not want him to stay too long in that time and place of fear.

The next student to read is Jonathan. His voice is scratchy and very low. I have to tell him several times to raise his voice, but it is a sad story so full of emotion that he breaks down several times in tears. He reads his story about seeing his father for the first time in many years. He describes the awkwardness, the strangeness of hugging a stranger. And then the joy of finally, finally being with his Dad in a loving embrace.

Some of the other students pat him on the back or walk over and give him a hug. Compassion, empathy, and understanding are in the room hovering over this class.

Young Erica seems very ready to read. I have had to push her hard at times to write her truth, her experience. She comes from Venezuela and she has become used to the quiet voice of the individual, not to speak of certain things – ever. I relate very much to Erica’s story as it’s similar to my own family’s story in Cuba. She takes a deep breath and looks down at her paper.

She almost knows it by heart. She begins to tell us of the day she learns by accident that she will be leaving and coming to the United States. Her parents are speaking in hushed voices but with their bedroom door open she can make out some of the conversation. They are worried and scared but they have made the decision. As she realizes they are talking about her not a neighbor or distant family member, she feels happy, sad, scared, excited – all at the same time. She lets us in slowly as her parents describe the hopeless and violent scene in the country and how they must save her before it’s too late to do anything.

The students all clap when she comes to the end of her story. They all know it has been a struggle for her to be so honest. She is smiling and very happy. I scan the room to see the reaction of the teachers in the room. I wonder if they had any idea what these kids have been through. They do now.

All have read except Josue. I look over at him. He waves me off. Josue? I can tell you want to try, but you lack the energy, or is it fear I see in your eyes? I’m not here to get you to do assignments, to help you pass your classes, but I am here to see if together we can make something magical happen. “Josue, tell me your story, please. What was it like in Honduras for you y su familia?

“No,” he says shakily. I move closer to him, put my hand on his shoulder and say in Spanish softly, “Es su turno, Josue. Tu lo puedes hacer.” The drama has been building in the room so all eyes are him. And you look up at me. I can see you’re trying to work up the courage to speak and finally you begin to read. You’re reading out loud! This is huge! I am elated!

Then I hear it: ”Josue, you can read that in English.” Who said that? My brain skids to a stop as Josue’s voice trails off abruptly. I scan the room carefully, looking into the eyes of every student. One by one their eyes shift uncomfortably. And then I see her. She is looking directly at Josue as if waiting for an answer. Yes, yes, I found her – Mrs. Batson, his ENL teacher. She is in the back of the room tutoring another student. How dare she? She has no idea what she had just done. Or does she? I think she does. I force her eyes to meet mine. Without a syllable, I communicate, “Do not say another word. NO, not one!!!” with my eyes. When this is over, I promise you, we will be having a conversation. But not now. Now I must snap Josue back into his reading.

I stand close to Josue and gently whisper, “Sigue en Espanol por favor. Es el idoma de nuestros antepasados orgullosos.” Thank God, you manage to compose yourself and draw up your courage again. You read your story and I can see it happening. The tears are falling down your cheeks; you wipe them away quickly with your sleeve but you don’t stop. That’s it, Josue. Get it all out. As he reads the couple of paragraphs he’s written, I feel transported by his words to a tiny village in Central America where he discovers that he will be leaving soon. Leaving for the United States – on a dangerous trip with many obstacles awaiting him. He walks through his small home and stares at his things and his relatives as if to somehow to memorize them, packing them in the suitcase of his mind to bring them with him.

You finish, there is a hush and then enormous applause breaks out in the room. The kids are all on your side. They know exactly what you are talking about. I look over at your teachers. We make eye contact. We know what this is like for you, Josue. ”Muy bien hecho, hijo!” — Well done, son!” Well done! TRIUMPH!

I pack up to head home, collecting my hugs from all the kids and thank yous from the teachers. It’s my last day of class and just like Josue, I pack the memories in my mind for safekeeping. Heading down the sterile school stairs, I begin to think about the experiences of the many, many brave young people who are forced to leave their beloved homes and extended families and friends and have been unceremoniously plunked into a high school on Long Island. Long Island, not New York City, where for generations immigrants have landed. Long Island, where in most cases they are certainly not welcomed, most times just ignorantly ignored.

As I get in my car and sit at the wheel, I start to feel anger surging at the base of my head. That’s where it always starts. And that phrase floats back into my brain. “No, Josue! In English!” I want to get home but all the way along the Meadowbrook, Loop Parkway and into Long Beach I can still hear your teacher saying, “No! Josue! In English!” They are well meaning, Josue. I know that and I hope you do, too. After all, they want you to learn English for a very important reason. They know you need it to pass your exams to move on to the next grade and maybe just maybe on to college if you try hard enough.

But tell me, what is it like to hear your teachers, guidance counselors, and others ask you to “speak English”? What is that doing to you? Do they understand how much you have been through to be sitting in that classroom? Is it forcing you to turn your back on your language, culture, and family? Will you be stripped of what makes you loved and special? Does it make you feel that anything “not English” or part of the American culture is bad? Are Spanish, Honduras and being Latino now bad? Will it force you eventually to be embarrassed of your country and heritage? Do you feel you are less than? Will self-hatred dig deep into your being as I have seen it do to others, to me? Espero que no — I hope not.

Helen bio

Using Brave Journeys with Seriously Wounded Students

by Alijan Ozkiral

While most of the ENL classes that made use of Brave Journeys eagerly embraced the work, we thought it would be useful to include this reflection by one of our fellows on working with students who were too wounded to meet the material right away.

After going through security at Hempstead High School’s main entrance, I went up to the main office on the second floor. I was to be escorted to B304, where my first English as New Language (ENL) class was to be held. The security guard and I waited for the second bell to ding. I noticed the bells in this high school were louder, more electric than I remember from my own high school. Across and to the left of the main office, we went up the stairs and made another left to get to the classroom. I shook the security guard’s hand and entered the room.

Twelve seats were gathered into a roundtable. I chose the seat second closest to the door, which became my permanent fixture each Wednesday morning thereafter. I surveyed the room and counted eight people. Two of them were Helen and Mr. Hogu, the facilitators for the Herstory/ ENL collaboration. There were only five students. Looking at the attendance sheet, I counted 12 students who were enrolled in the ENL course. As I looked toward Helen to ask her about the missing students, she began speaking in the language of her parents.

“Hola, soy Helen. Mi padre viene de Cuba,” she started. The student across from me raised his head, startled by Helen’s fluency. “Vamos a empezar introducciones. Por favor tell us your names, where you’re from, how long you’ve been in America, and what your dream is.”

The student across from me spoke first. “My name is Julio. I’m from the Dominican Republic and I’ve been here for three years.” He wore a grey, graphic sweatshirt with a neon green goblin on the front. His headphones were in his ears. “I haven’t seen my family in two years.”

The class nodded, then went silent. We turned toward the student to the left of Julio.

“Oh! My name is Martin. I’m from Guatemala, and I’ve been here for three years. This is my first year in school here, though.” He wore a black sweater with a polo underneath. His headphones were in his ears. “I want to be a math teacher.”

Across from Martin, a student in a bright blue sweatshirt, also with headphones in his ears, laughed. Mr. Hogu snapped, “Andy!”

“Sorry, Mr. Hogu. My name is Andy. I’m from El Salvador, and I have been here for three years.”

He paused for a moment, perhaps to think of his dream, and Helen interjected. “Andy, you were a Herstory student last year, too, right?”

Andy nodded. “Yes, Ms. Helen.”

“Does that mean you have some writing for us already?”

“No, Ms. Helen. I lost it.”

“You lost it?” Helen said. She sounded surprised but not angry, speaking to Andy as a parent does to an enthusiastic child that is not theirs. “That’s all right. We’ll get you to write some more this semester, don’t worry. And what is your dream, Andy?”

“I want to be a nurse!” He laughed after saying it, as if he didn’t quite believe it himself. But each time we asked him his dream thereafter, he always said he wanted to be a nurse to help people.

At the end of the table, across from one another, sat the last two students. They were dressed plainly with each wearing a simple hoodie, sans headphones.

“Lobos, you go!” said Andy.

“My name is Jordin. I’m from Honduras and I’ve been here for two years. I want to be a mechanic.” His sentences were short and his words concise and quiet. I noticed that he introduced himself as Jordin, though everyone calls him Lobos – including his teacher, Mr. Hogu.

Helen prodded further. “What kind of mechanic? Planes, cars?”

“Cars,” responded Jordin, with a shy lull to his response.

The last student began his introduction. Unlike the other students, he spoke mostly in English. “My name is Cristian. I’m from El Salvador and I have been in America for three years. I want to be a pilot.” His English was understandably rough. Though he stammered through his introduction, his smile at the end captivated me.

We began reading aloud from Brave Journeys to get the class started. Helen asked if we should read in English or in Spanish.

“Spanish! Only Spanish!” shouted the students. Julio smacked his fist to the table proclaiming, “Spanish!” This would be the first moment that I would learn of his combativeness.

There was a quieter voice, barely able to reach my ears over the other students’ proclamations. “English. English.” Of course, it was Cristian.

Julio began to read the first story in Spanish. After two paragraphs, Cristian took over, reading aloud in English. He read slowly but dedicated himself to annunciating each word. Occasionally, Mr. Hogu and I would interrupt to correct his pronunciation, in which case Cristian repeated the word and continued to read.

During the following weeks, the classes ran similarly. Students would attend inconsistently. One week, the only student to show up was Cristian. In the weeks when the attendance was healthier, all students would refuse to write or read in English – except for Cristian.

***

“This week we’re going to read a story that’s written like a poem. It’s called ‘Every Time I Looked Back.’” After several weeks, the students still had not produced any writing save for Cristian’s paragraph on returning home to El Salvador. I hoped that the anaphora in “Every Time I Looked Back” would spark some new interest.

“Okay, class, we’re going to begin reading,” I announced. “I’m going to start reading then I’ll pick someone to keep going.” I began to read:

Many people judge without knowing . . .

They don’t know the story or the thoughts, the sensations, the past, or feelings . . .

Of the quiet girl or the rebel boy,

Of the smart girl or the boy that doesn’t push himself . . .

“What is this? It’s just a list.” Martin interjected.

“It’s like a poem,” I reiterated. “Maybe this is a good time to talk about the narrative functions that are going on here.”

Mr. Hogu wrested control from me and began, “Can anyone tell me what the narrator is doing?” He was met with silence.

“It’s juxtaposition. The author is comparing two things that are different to make an effect,” said Mr. Hogu.

“But it’s just a list!” said Martin.

“No, Martin. It is more than a list. The author is doing something deliberate to make a point. This list is a reflection on things she has seen and she is comparing them to argue her point. Her point is . . . ”

Martin cut him off. “What are you talking about? There isn’t anything happening here! It’s a list and she’s just saying things that are different. There’s no effect here. It’s just rambling and no structure.”

Martin’s voice increased in volume and he spoke faster as he went on. His words devolved into unintelligible rambling.

Helen, Mr. Hogu, and I shook our heads.

“Can you say it again slower? I’m having trouble understanding what you’re trying to say,” said Mr. Hogu.

Martin threw his hands up and let them crash onto the desk. “No, no. Just read. Let’s keep going.”

“Use some other words. Explain it again,” said Julio and Cristian in unison.

“Ofthedistractedorhyperactive, oftheobedientorthedisobedient,” Martin resumed reading with an intense pace.

“Martin, just slow down and try explaining yourself again,” said Cristian.

“Okay, okay. I just don’t get why we have to read things like this. I don’t think it is good. I don’t think it explains anything clearly. I don’t think the point is being made. And, I don’t like how you all come here and try to get our writing and leave. This author is making her juxtapositions and there’s no point to it. How is this a reflection at all? What is she reflecting on? These are random pairings and pointing out random things.” He breathed in and shifted his eyes around the room.

He continued, “You keep telling us that writing will ‘help our traumas’ and help other people with the same traumas, but why do we want to do that? This author’s trauma isn’t my trauma. I buried my trauma; I don’t even feel it anymore! I don’t want to have to look at it again. I don’t want to think about it again. As long as I don’t think about it then it never happened. So why should I have to write it? Why should I have to read any of this anyway? It’s not even good.”

Mr. Hogu stood up. I took out my notebook and began to take notes.

“Listen, Martin,” Mr. Hogu said. Martin turned his head away. “All of you, this is important, so listen to me. Okay?”

Mr. Hogu continued, “Lists are reflections. We are invited into the author’s universe. Maybe the problem is that the author isn’t listing her reflection explicitly, but in just seeing her list, in seeing her observations, we are learning about life. It is a reflection because she’s thinking about all the people she has encountered and maybe how she judged these people and how she judged herself and how she knows – how she knows now – that she was wrong to do that. You know, this is something she learned by writing. She learned this by doing.”

“But!” said Martin. The rest of the class looked at him.

“No!” Mr. Hogu took a deep breath. “You guys are too afraid to put your best on the page, to be judged for your writing and to be judged for your traumas. Your work on the page is for us, sure, but it is also for you! Your traumas are with you forever. You think we are born fully formed? Do you think I was born a teacher?”

Mr. Hogu paused briefly. The class shifted their gaze downwards, unspeaking, then looked back up.

Mr. Hogu began again. “No! I had to work hard to become a teacher. I had to work hard and I had to make mistakes and deal with my own traumas to become who I am. It is what being a man is! Being a man is working on yourself. None of us are fully formed. You are refusing to do the work you need to do to become a man. To become an adult. To become a person! You can’t bury your traumas because you will always be afraid of them. They will always hold you back unless you make them a part of you. This author did that! You guys might not want to do it now, you guys might not want to do it later. But, if you guys want to become anything at all, and most of all if you want to become men and not boys, you will need to learn to do it. You have to. So, it’s not for us. No, no, no. It can’t be for us. We just want to help you do the work.”

The class finally began to write. Julio had produced two sentences. Martin had produced one paragraph. Lobos forgot his notebook at home. And Cristian revised his first paragraph and wrote an additional one.

Helen asked, “Okay, class, what did everyone write?”

Cristian led the group. “I wrote about El Salvador. I wrote about how I want to go home and how my grandma died while I was here. I couldn’t say goodbye.”

“Oh, Cristian, I’m so sorry. But can I ask some more questions?” said Helen. Cristian nodded. “Do you want to stay in El Salvador when you go back?”

“No, Ms. Helen. “I want to come back here. I like my friends here and I want to keep working here.”

“Oh, then maybe when we’re doing revisions you can write about how you want to go back to El Salvador. Then, as you’re finally going back, or maybe before – I don’t know, it’s your story, Cristian – then you can have a surprise twist where you say, ‘But, I don’t want to stay there forever. I want to come back to America.’” Cristian’s face shined.

“Ms. Helen, I really like that idea! You’re right. That would be good! I will work on it as soon as I can.”

“I can’t wait to read it, Cristian!” said Helen. The bell rang before anyone else could share.

After the shrieking of the bell ceased, Helen said, “Okay, class. Next week we’re all going to start by sharing what we wrote. I’m very excited because we finally have some stuff to get the ball rolling with.”

As Cristian walked over to the door, I stopped him and shook his hand. “Cristian, thank you for everything you did today. I think we were able to have a good class because of you. I can’t wait to hear what you have next week.”

“Thank you, teacher!” he said. Then he walked out the door.

I drove home that day with a smile on my face. So, this is what it feels like when a teacher says that he has a bright class, I thought to myself.

The following week, Cristian was absent.

“Hey, class. Where’s Cristian this week?” I said.

“Oh, he moved,” responded Julio.

“What do you mean he moved?”

“His parents had to move. I think he might go to school in Queens or something now?”

Helen said, “Does anyone have any of his contact information or anything? I was really looking forward to his story.” The students’ faces were blank. “Really? No one has their friend’s phone number or email?”

The most diligent student in the class had left. His story is unreachable – but we know it’s there. And we know it must be good. He had put in the work to become someone, after all.

Beyond Accents and Silences

By Natalia Chamorro

A high school auditorium is filled by cheerful students who are chatting, laughing, and checking their phones, until one of them walks to the podium. Shy yet confident, she begins to read out in Spanish a story that she wrote, displayed in English on the projector screen. As the student continues reading, silence grows. Teachers turn around to check on their students, now caught in the narration of the teenage girl at the podium. Her story echoes a young voice whose experiences and thoughts resonate with her peers sitting in front of her.

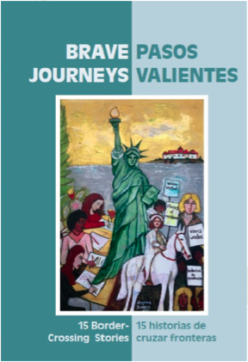

Echoing the experience of the captivated crowd in the auditorium, something similar happens to both students and educators when they read through one of the 15 bilingual stories of Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes, a book that tells the stories of immigrant teenagers arriving in the United States from Latin America. The role of student-reader does not seem far from the one of student-author when we think about how writing and reading are not only skills to learn in school, but experiences of communication and contact that go beyond transmitting information. They are able to convey feelings, nurture empathy, and make room for understanding.

Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes is the collective work of students, educators, and writers from Herstory Writers Workshop, an organization that connects writing with empathy and makes it a platform for all voices. Through the initiative of English Language Learners (ELL) educators, this book responds to the wide need for bilingual immigrant literature that inspires both teachers and students to engage in reading and writing activities. In the words of Long Island teacher Dafny Irizarry, whose students created the book over a period of years, and who now uses the book in her classes:

“Writers write about what they know, what they care about, and about what it is near and dear to their hearts. So if we introduce ELL students to writing, in that manner, about the things that they live and they know about, they develop a liking for writing of what matters for them.”

There is a transparent quality of young writing that reflects on the experiences, questions, and challenges we all go through as we become adults, something many immigrant kids learn fast through unexpected family separation. While much of the immigrant literature written by Latino writers includes touching memories of arrival as well, it is usually written from an adult perspective and in a different, yet equally difficult time. The reality of the stories narrated in Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes appeals to the complexity, challenges and beauty of life, from surprisingly strong young eyes, told by those who, like every teenager, have had to cross over obstacles to reach their dreams.

What is to read a story that could have written by your student?

Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes has become a powerful tool for educators to better understand their immigrant students in the United States on a more humane level. For students in the general population, it opens a window that allows them to see beyond accents and silences.

In the high school auditorium, students have respectfully listened to their peers’ stories. It is hard to imagine what is to read a piece of your life in front of so many people. The teachers say their final words, and one of them expresses how much learning the students’ stories has helped her to understand their situation better, to become more compassionate and patient. Another teacher mentions that we’ll have many teachers in life, and that today, these students were his teachers.

Writing a story, you become the author of your past, present and future.

If everyone is an intrinsic storyteller, because everyone has a story to tell, the story I carry within me wakes up when I read or listen those of others. As one high school student reflected after having read her story in front a crowd:

Reading your story out loud is like tearing off the thorn of a rose from your skin: it hurts but you can feel how you are starting to heal already.

“I also have a story to tell, but today I will read about my future,” said one of the last students who went up to the podium.

Brave Journeys to the Rescue

by Dawn Attard

I know you get it. I know you have felt the pressure so many other high school ELA teachers feel in June. The Regents is looming and you are struggling to break the monotony of skill and drill. I was losing my kids as they were tired of reading through Regents texts they had likely seen before. My ELL class was in particular need of a change of pace and perspective:

“Ms., how many paragraphs does it need to be?”

“Ms., I still don’t get what I’m supposed to do.”

“Ms., I just don’t understand this story.”

It was the same; they were frustrated and so was I – for them, and for myself as I struggled to help them “get it.” The ones who vocalize their confusion are easy – right? I can help, I can guide, I can review, show, model – whatever it takes. I run from group to group. But what about the kids who don’t even know how to communicate their confusion? The kids who just sit there not knowing – that’s who I am still trying to reach on June 14th, just days prior to an exam they have already failed (some more than once).

I have the meeting scheduled. My search for something outside myself, outside the confines of my daily structure, has led me toHerstory Writers Workshop – an amazing organization looking to give voice to the underserved, the unheard voices they hope will “break the silence” in an effort to “change hearts, minds, and policies.”

We talk; we try to find a place for me within this humanitarian project. Erika, Herstory’s fearless leader, casually mentions Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes – a bilingual text she has recently published featuring stories written by actual students from Central Islip and Patchogue-Medford High Schools, and I’m struck. I think my unfettered enthusiasm has caught Erika somewhat off guard, because she doesn’t yet realize that I have found my solution. You know, that teacher part of your brain that is never turned off? Well, there goes mine, planning lessons and thinking how wonderful it will be to share this with my kids. After some light pleading, Erika graciously agrees to sell me a class set of the book at a heavily discounted rate, and I leave with my hands full and my mind racing.

I’m back in the classroom, text in hand. “Today, we’re going to do something a little different.” Immediate excitement because they think we’re done with Regents prep. They’re wrong. But, it’s okay. They’ll see. I distribute the text as I try to explain its magnitude and value. I can’t possibly do it within the few minutes I have designated as part of my lesson. But I try.

“So, this one teacher over at Central Islip High School had asked her students during the holidays to hang an ornament on a tree that expressed something they were thankful for. When all of the students in her ELL class wrote about their gratitude, not for a new pair of sneakers, or for the latest iPhone, but only about being reunited with their mothers and fathers, this teacher was moved and saw that these students had stories that needed to be heard, that they had something that needed to be shared.

“So, she contacted Herstory, which is this wonderful organization whose goal is to help develop and gather the stories of members of Long Island’s most vulnerable populations. The organization sent facilitators into the school and worked for weeks and months helping students communicate their stories in a way that allows the reader to walk in their shoes. The stories were then shared at different events across the island, and because of the importance and impact of the stories, there was a demand that they be published, which Herstory did as this really breathtaking collection of memoirs called Brave Journeys or Pasos valientes, and that’s what I have here for you today.”

Then come the questions:

“Central Islip? I think I’ve heard of that. That’s close, right?”

“Yes, not far. In Suffolk County near where I live. The school is diverse. Much like our own.”

“Ms.,” (pointing to redacted names), “What are these black bars all over?”

“Well, that is to protect the identity of the students. They’re sharing something very personal and given today’s world, there was some fear in sharing their stories.”

“So, these are real kids? Real stories?”

“Yup, real stories. Real kids just like you.” (I take some time to remind them what a memoir is).

Those looks of confusion start to turn to genuine interest. When I remind them that we’re still in the midst of our Regents Prep Unit and will be using the Brave Journeys text to help develop central idea statements, I am met with much less resistance than I imagined.

“Let’s read the first story together. It’s short. Who wants to go first?”

The usual silence, then, “Can we read it in Spanish?” Since the majority of students in my class (all but two) speak Spanish, I agree. And I’m excited. My co-teacher has a decent grasp of the language and I know that I and the one other non-Spanish-speaking student present will at least get to enjoy this beautiful language while still having the benefit of the English version.

“I’ll go first.” I’m not surprised when I hear the voice. He’s always willing to help get us going. He begins. I’m smiling as I read along. What these words sound like in my head (or when I try to speak them) is not nearly as beautiful as what I hear.

A voice interrupts. “I want to try.” It’s the girl next to him. She senses the focus. She knows everyone is listening and she wants to be a part of it, too. Again, I’m smiling.

This time, she stops herself and turning to her friend, with a daring, somewhat mischievous tone says, “Now, you try, it’s your turn.” And I think, “Good luck, you’ll never get him to read.” But she does!

There’s an exchange in Spanish that I miss and though reluctantly, he does it – he reads, out loud. Again, I’m smiling. They all stumble. The co-teacher helps them. But they don’t stop. They don’t hesitate. They don’t want to give up. There’s one more student who makes sure he gets a turn before we’re finished, and there goes the smile again.

“Wow, so that was pretty amazing, right? I’m so impressed by you guys. Thank you for sharing your language with me, that was really great.”

“But Ms., you didn’t try.” I pretend I don’t hear them.

“Ms., it’s your turn.”

“No, no. You don’t want to hear me. You all speak so beautifully, I would ruin it.” And then it hits me. They’ve turned the tables. I’m the student. I’m them and I “get it.” I get how they feel when they’re asked to read in a language with which they’re not comfortable. I always try to understand them culturally – that’s the benefit of my job; I’m learning their ways, their beliefs, religion, customs on a daily basis. But how often can we say we understand our students on a deeper, emotional level? In this instant, though brief, I did. I truly understood the anxiety my students must endure daily as they are asked to navigate unfamiliarity – whether linguistically or conceptually. They sense my embarrassment and now we’re all smiling.

“Okay, okay.” And I work out a terrible, “If we look at ‘nunca te olvidare’ and this young girl’s statement that ‘en ese momento no se te ocurre si podrias llegar a conocer la historia de la vida,’ how can we interpret that and apply an understanding of central idea?”

They laugh at my Spanish, but it’s okay because I’ve transitioned back to our Regents task and they don’t mind. They’re still with me.

With what time is left, I distribute the writing activity which models statements and ask students to create their own. We move from small group to small group, offering individual instruction, and the results are astounding. There’s no more, “Ms., I don’t understand the story.” This immigrant experience is familiar to many of them and especially to their families. I go back to the same routine.

“So, the central idea is clear; we can use the model to . . . blah, blah, blah.” They get that. We’re past it. The more important questions now are, “How? How do you know?” “Where’s your evidence?” “You can’t just make a claim without properly supporting it.”

I might as well record myself at the beginning of the year and save the trouble – it’s a daily hurdle. That’s their struggle and that was the goal of this lesson. And, this time, I can already see the difference.

As I walk the room, I see the clarity and emotion in their conclusions and in their connections:

“I know she’s strong because it says she was only eight years old when she found out her father was killed.”

Many of them write:

“It is obvious this girl had to make sacrifices because she risked the journey even though she knew there were many women who had been raped on the way.”

Another adds:

“She sacrificed having to leave her grandmother who raised her and was the only person who loved her unconditionally, and who she knew she would probably never see again.”

I can see the realization, the sadness, the seriousness on their faces when they remember that this story is “real.” That it happened to a “real kid” just like them. I breathe a sigh of relief for the first time in weeks and I remind them that they do “get it,” they do “know what to do.” I try to instill a sense of confidence that I know they need and that I hope will bring them success, not just on the Regents.

Time is running out. I’m “closing up” my lesson and I’m left with “thank yous.” I’m not surprised. They’re sweet kids. I often hear, “Thank you, Ms., have a good day.” But this time the thank yous are followed by, “Ya know, that was really cool. I can’t remember the last time I got to read a story in Spanish. We speak Spanish all the time, but we don’t get to read it like this.” The sentiment is echoed as they file out of the classroom. And we’re all smiling. “Have a great day, guys. Be good.”

A former chairperson would always ask me what my “So, what?” was. We’d review lessons and she’d say, “So, what?” It drove me crazy; it took me a long time to get what she meant and now that “So, what?” is ingrained in every lesson I prepare, in everything I do. What’s the takeaway? Why am I doing this? What is truly important? And this time, my “So, what?” is this: they engaged, they connected, they learned, I learned, we laughed, and they left with confidence and perhaps with new feelings of empathy.

I took a chance with a new text and better understand now the value Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes offers to racially and culturally diverse students as they search for meaning in a foreign land. And perhaps, more importantly, the value the text offers to students from racially and culturally homogeneous backgrounds who may lack the understanding and empathy needed to function well in today’s world.