by Alijan Ozkiral

While most of the ENL classes that made use of Brave Journeys eagerly embraced the work, we thought it would be useful to include this reflection by one of our fellows on working with students who were too wounded to meet the material right away.

After going through security at Hempstead High School’s main entrance, I went up to the main office on the second floor. I was to be escorted to B304, where my first English as New Language (ENL) class was to be held. The security guard and I waited for the second bell to ding. I noticed the bells in this high school were louder, more electric than I remember from my own high school. Across and to the left of the main office, we went up the stairs and made another left to get to the classroom. I shook the security guard’s hand and entered the room.

Twelve seats were gathered into a roundtable. I chose the seat second closest to the door, which became my permanent fixture each Wednesday morning thereafter. I surveyed the room and counted eight people. Two of them were Helen and Mr. Hogu, the facilitators for the Herstory/ ENL collaboration. There were only five students. Looking at the attendance sheet, I counted 12 students who were enrolled in the ENL course. As I looked toward Helen to ask her about the missing students, she began speaking in the language of her parents.

“Hola, soy Helen. Mi padre viene de Cuba,” she started. The student across from me raised his head, startled by Helen’s fluency. “Vamos a empezar introducciones. Por favor tell us your names, where you’re from, how long you’ve been in America, and what your dream is.”

The student across from me spoke first. “My name is Julio. I’m from the Dominican Republic and I’ve been here for three years.” He wore a grey, graphic sweatshirt with a neon green goblin on the front. His headphones were in his ears. “I haven’t seen my family in two years.”

The class nodded, then went silent. We turned toward the student to the left of Julio.

“Oh! My name is Martin. I’m from Guatemala, and I’ve been here for three years. This is my first year in school here, though.” He wore a black sweater with a polo underneath. His headphones were in his ears. “I want to be a math teacher.”

Across from Martin, a student in a bright blue sweatshirt, also with headphones in his ears, laughed. Mr. Hogu snapped, “Andy!”

“Sorry, Mr. Hogu. My name is Andy. I’m from El Salvador, and I have been here for three years.”

He paused for a moment, perhaps to think of his dream, and Helen interjected. “Andy, you were a Herstory student last year, too, right?”

Andy nodded. “Yes, Ms. Helen.”

“Does that mean you have some writing for us already?”

“No, Ms. Helen. I lost it.”

“You lost it?” Helen said. She sounded surprised but not angry, speaking to Andy as a parent does to an enthusiastic child that is not theirs. “That’s all right. We’ll get you to write some more this semester, don’t worry. And what is your dream, Andy?”

“I want to be a nurse!” He laughed after saying it, as if he didn’t quite believe it himself. But each time we asked him his dream thereafter, he always said he wanted to be a nurse to help people.

At the end of the table, across from one another, sat the last two students. They were dressed plainly with each wearing a simple hoodie, sans headphones.

“Lobos, you go!” said Andy.

“My name is Jordin. I’m from Honduras and I’ve been here for two years. I want to be a mechanic.” His sentences were short and his words concise and quiet. I noticed that he introduced himself as Jordin, though everyone calls him Lobos – including his teacher, Mr. Hogu.

Helen prodded further. “What kind of mechanic? Planes, cars?”

“Cars,” responded Jordin, with a shy lull to his response.

The last student began his introduction. Unlike the other students, he spoke mostly in English. “My name is Cristian. I’m from El Salvador and I have been in America for three years. I want to be a pilot.” His English was understandably rough. Though he stammered through his introduction, his smile at the end captivated me.

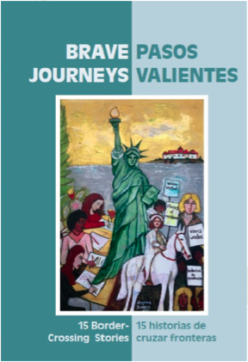

We began reading aloud from Brave Journeys to get the class started. Helen asked if we should read in English or in Spanish.

“Spanish! Only Spanish!” shouted the students. Julio smacked his fist to the table proclaiming, “Spanish!” This would be the first moment that I would learn of his combativeness.

There was a quieter voice, barely able to reach my ears over the other students’ proclamations. “English. English.” Of course, it was Cristian.

Julio began to read the first story in Spanish. After two paragraphs, Cristian took over, reading aloud in English. He read slowly but dedicated himself to annunciating each word. Occasionally, Mr. Hogu and I would interrupt to correct his pronunciation, in which case Cristian repeated the word and continued to read.

During the following weeks, the classes ran similarly. Students would attend inconsistently. One week, the only student to show up was Cristian. In the weeks when the attendance was healthier, all students would refuse to write or read in English – except for Cristian.

***

“This week we’re going to read a story that’s written like a poem. It’s called ‘Every Time I Looked Back.’” After several weeks, the students still had not produced any writing save for Cristian’s paragraph on returning home to El Salvador. I hoped that the anaphora in “Every Time I Looked Back” would spark some new interest.

“Okay, class, we’re going to begin reading,” I announced. “I’m going to start reading then I’ll pick someone to keep going.” I began to read:

Many people judge without knowing . . .

They don’t know the story or the thoughts, the sensations, the past, or feelings . . .

Of the quiet girl or the rebel boy,

Of the smart girl or the boy that doesn’t push himself . . .

“What is this? It’s just a list.” Martin interjected.

“It’s like a poem,” I reiterated. “Maybe this is a good time to talk about the narrative functions that are going on here.”

Mr. Hogu wrested control from me and began, “Can anyone tell me what the narrator is doing?” He was met with silence.

“It’s juxtaposition. The author is comparing two things that are different to make an effect,” said Mr. Hogu.

“But it’s just a list!” said Martin.

“No, Martin. It is more than a list. The author is doing something deliberate to make a point. This list is a reflection on things she has seen and she is comparing them to argue her point. Her point is . . . ”

Martin cut him off. “What are you talking about? There isn’t anything happening here! It’s a list and she’s just saying things that are different. There’s no effect here. It’s just rambling and no structure.”

Martin’s voice increased in volume and he spoke faster as he went on. His words devolved into unintelligible rambling.

Helen, Mr. Hogu, and I shook our heads.

“Can you say it again slower? I’m having trouble understanding what you’re trying to say,” said Mr. Hogu.

Martin threw his hands up and let them crash onto the desk. “No, no. Just read. Let’s keep going.”

“Use some other words. Explain it again,” said Julio and Cristian in unison.

“Ofthedistractedorhyperactive, oftheobedientorthedisobedient,” Martin resumed reading with an intense pace.

“Martin, just slow down and try explaining yourself again,” said Cristian.

“Okay, okay. I just don’t get why we have to read things like this. I don’t think it is good. I don’t think it explains anything clearly. I don’t think the point is being made. And, I don’t like how you all come here and try to get our writing and leave. This author is making her juxtapositions and there’s no point to it. How is this a reflection at all? What is she reflecting on? These are random pairings and pointing out random things.” He breathed in and shifted his eyes around the room.

He continued, “You keep telling us that writing will ‘help our traumas’ and help other people with the same traumas, but why do we want to do that? This author’s trauma isn’t my trauma. I buried my trauma; I don’t even feel it anymore! I don’t want to have to look at it again. I don’t want to think about it again. As long as I don’t think about it then it never happened. So why should I have to write it? Why should I have to read any of this anyway? It’s not even good.”

Mr. Hogu stood up. I took out my notebook and began to take notes.

“Listen, Martin,” Mr. Hogu said. Martin turned his head away. “All of you, this is important, so listen to me. Okay?”

Mr. Hogu continued, “Lists are reflections. We are invited into the author’s universe. Maybe the problem is that the author isn’t listing her reflection explicitly, but in just seeing her list, in seeing her observations, we are learning about life. It is a reflection because she’s thinking about all the people she has encountered and maybe how she judged these people and how she judged herself and how she knows – how she knows now – that she was wrong to do that. You know, this is something she learned by writing. She learned this by doing.”

“But!” said Martin. The rest of the class looked at him.

“No!” Mr. Hogu took a deep breath. “You guys are too afraid to put your best on the page, to be judged for your writing and to be judged for your traumas. Your work on the page is for us, sure, but it is also for you! Your traumas are with you forever. You think we are born fully formed? Do you think I was born a teacher?”

Mr. Hogu paused briefly. The class shifted their gaze downwards, unspeaking, then looked back up.

Mr. Hogu began again. “No! I had to work hard to become a teacher. I had to work hard and I had to make mistakes and deal with my own traumas to become who I am. It is what being a man is! Being a man is working on yourself. None of us are fully formed. You are refusing to do the work you need to do to become a man. To become an adult. To become a person! You can’t bury your traumas because you will always be afraid of them. They will always hold you back unless you make them a part of you. This author did that! You guys might not want to do it now, you guys might not want to do it later. But, if you guys want to become anything at all, and most of all if you want to become men and not boys, you will need to learn to do it. You have to. So, it’s not for us. No, no, no. It can’t be for us. We just want to help you do the work.”

The class finally began to write. Julio had produced two sentences. Martin had produced one paragraph. Lobos forgot his notebook at home. And Cristian revised his first paragraph and wrote an additional one.

Helen asked, “Okay, class, what did everyone write?”

Cristian led the group. “I wrote about El Salvador. I wrote about how I want to go home and how my grandma died while I was here. I couldn’t say goodbye.”

“Oh, Cristian, I’m so sorry. But can I ask some more questions?” said Helen. Cristian nodded. “Do you want to stay in El Salvador when you go back?”

“No, Ms. Helen. “I want to come back here. I like my friends here and I want to keep working here.”

“Oh, then maybe when we’re doing revisions you can write about how you want to go back to El Salvador. Then, as you’re finally going back, or maybe before – I don’t know, it’s your story, Cristian – then you can have a surprise twist where you say, ‘But, I don’t want to stay there forever. I want to come back to America.’” Cristian’s face shined.

“Ms. Helen, I really like that idea! You’re right. That would be good! I will work on it as soon as I can.”

“I can’t wait to read it, Cristian!” said Helen. The bell rang before anyone else could share.

After the shrieking of the bell ceased, Helen said, “Okay, class. Next week we’re all going to start by sharing what we wrote. I’m very excited because we finally have some stuff to get the ball rolling with.”

As Cristian walked over to the door, I stopped him and shook his hand. “Cristian, thank you for everything you did today. I think we were able to have a good class because of you. I can’t wait to hear what you have next week.”

“Thank you, teacher!” he said. Then he walked out the door.

I drove home that day with a smile on my face. So, this is what it feels like when a teacher says that he has a bright class, I thought to myself.

The following week, Cristian was absent.

“Hey, class. Where’s Cristian this week?” I said.

“Oh, he moved,” responded Julio.

“What do you mean he moved?”

“His parents had to move. I think he might go to school in Queens or something now?”

Helen said, “Does anyone have any of his contact information or anything? I was really looking forward to his story.” The students’ faces were blank. “Really? No one has their friend’s phone number or email?”

The most diligent student in the class had left. His story is unreachable – but we know it’s there. And we know it must be good. He had put in the work to become someone, after all.