by Dawn Attard

I know you get it. I know you have felt the pressure so many other high school ELA teachers feel in June. The Regents is looming and you are struggling to break the monotony of skill and drill. I was losing my kids as they were tired of reading through Regents texts they had likely seen before. My ELL class was in particular need of a change of pace and perspective:

“Ms., how many paragraphs does it need to be?”

“Ms., I still don’t get what I’m supposed to do.”

“Ms., I just don’t understand this story.”

It was the same; they were frustrated and so was I – for them, and for myself as I struggled to help them “get it.” The ones who vocalize their confusion are easy – right? I can help, I can guide, I can review, show, model – whatever it takes. I run from group to group. But what about the kids who don’t even know how to communicate their confusion? The kids who just sit there not knowing – that’s who I am still trying to reach on June 14th, just days prior to an exam they have already failed (some more than once).

I have the meeting scheduled. My search for something outside myself, outside the confines of my daily structure, has led me toHerstory Writers Workshop – an amazing organization looking to give voice to the underserved, the unheard voices they hope will “break the silence” in an effort to “change hearts, minds, and policies.”

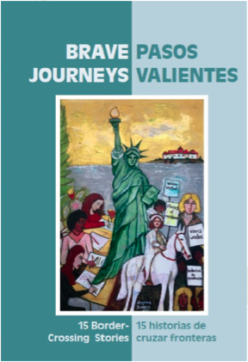

We talk; we try to find a place for me within this humanitarian project. Erika, Herstory’s fearless leader, casually mentions Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes – a bilingual text she has recently published featuring stories written by actual students from Central Islip and Patchogue-Medford High Schools, and I’m struck. I think my unfettered enthusiasm has caught Erika somewhat off guard, because she doesn’t yet realize that I have found my solution. You know, that teacher part of your brain that is never turned off? Well, there goes mine, planning lessons and thinking how wonderful it will be to share this with my kids. After some light pleading, Erika graciously agrees to sell me a class set of the book at a heavily discounted rate, and I leave with my hands full and my mind racing.

I’m back in the classroom, text in hand. “Today, we’re going to do something a little different.” Immediate excitement because they think we’re done with Regents prep. They’re wrong. But, it’s okay. They’ll see. I distribute the text as I try to explain its magnitude and value. I can’t possibly do it within the few minutes I have designated as part of my lesson. But I try.

“So, this one teacher over at Central Islip High School had asked her students during the holidays to hang an ornament on a tree that expressed something they were thankful for. When all of the students in her ELL class wrote about their gratitude, not for a new pair of sneakers, or for the latest iPhone, but only about being reunited with their mothers and fathers, this teacher was moved and saw that these students had stories that needed to be heard, that they had something that needed to be shared.

“So, she contacted Herstory, which is this wonderful organization whose goal is to help develop and gather the stories of members of Long Island’s most vulnerable populations. The organization sent facilitators into the school and worked for weeks and months helping students communicate their stories in a way that allows the reader to walk in their shoes. The stories were then shared at different events across the island, and because of the importance and impact of the stories, there was a demand that they be published, which Herstory did as this really breathtaking collection of memoirs called Brave Journeys or Pasos valientes, and that’s what I have here for you today.”

Then come the questions:

“Central Islip? I think I’ve heard of that. That’s close, right?”

“Yes, not far. In Suffolk County near where I live. The school is diverse. Much like our own.”

“Ms.,” (pointing to redacted names), “What are these black bars all over?”

“Well, that is to protect the identity of the students. They’re sharing something very personal and given today’s world, there was some fear in sharing their stories.”

“So, these are real kids? Real stories?”

“Yup, real stories. Real kids just like you.” (I take some time to remind them what a memoir is).

Those looks of confusion start to turn to genuine interest. When I remind them that we’re still in the midst of our Regents Prep Unit and will be using the Brave Journeys text to help develop central idea statements, I am met with much less resistance than I imagined.

“Let’s read the first story together. It’s short. Who wants to go first?”

The usual silence, then, “Can we read it in Spanish?” Since the majority of students in my class (all but two) speak Spanish, I agree. And I’m excited. My co-teacher has a decent grasp of the language and I know that I and the one other non-Spanish-speaking student present will at least get to enjoy this beautiful language while still having the benefit of the English version.

“I’ll go first.” I’m not surprised when I hear the voice. He’s always willing to help get us going. He begins. I’m smiling as I read along. What these words sound like in my head (or when I try to speak them) is not nearly as beautiful as what I hear.

A voice interrupts. “I want to try.” It’s the girl next to him. She senses the focus. She knows everyone is listening and she wants to be a part of it, too. Again, I’m smiling.

This time, she stops herself and turning to her friend, with a daring, somewhat mischievous tone says, “Now, you try, it’s your turn.” And I think, “Good luck, you’ll never get him to read.” But she does!

There’s an exchange in Spanish that I miss and though reluctantly, he does it – he reads, out loud. Again, I’m smiling. They all stumble. The co-teacher helps them. But they don’t stop. They don’t hesitate. They don’t want to give up. There’s one more student who makes sure he gets a turn before we’re finished, and there goes the smile again.

“Wow, so that was pretty amazing, right? I’m so impressed by you guys. Thank you for sharing your language with me, that was really great.”

“But Ms., you didn’t try.” I pretend I don’t hear them.

“Ms., it’s your turn.”

“No, no. You don’t want to hear me. You all speak so beautifully, I would ruin it.” And then it hits me. They’ve turned the tables. I’m the student. I’m them and I “get it.” I get how they feel when they’re asked to read in a language with which they’re not comfortable. I always try to understand them culturally – that’s the benefit of my job; I’m learning their ways, their beliefs, religion, customs on a daily basis. But how often can we say we understand our students on a deeper, emotional level? In this instant, though brief, I did. I truly understood the anxiety my students must endure daily as they are asked to navigate unfamiliarity – whether linguistically or conceptually. They sense my embarrassment and now we’re all smiling.

“Okay, okay.” And I work out a terrible, “If we look at ‘nunca te olvidare’ and this young girl’s statement that ‘en ese momento no se te ocurre si podrias llegar a conocer la historia de la vida,’ how can we interpret that and apply an understanding of central idea?”

They laugh at my Spanish, but it’s okay because I’ve transitioned back to our Regents task and they don’t mind. They’re still with me.

With what time is left, I distribute the writing activity which models statements and ask students to create their own. We move from small group to small group, offering individual instruction, and the results are astounding. There’s no more, “Ms., I don’t understand the story.” This immigrant experience is familiar to many of them and especially to their families. I go back to the same routine.

“So, the central idea is clear; we can use the model to . . . blah, blah, blah.” They get that. We’re past it. The more important questions now are, “How? How do you know?” “Where’s your evidence?” “You can’t just make a claim without properly supporting it.”

I might as well record myself at the beginning of the year and save the trouble – it’s a daily hurdle. That’s their struggle and that was the goal of this lesson. And, this time, I can already see the difference.

As I walk the room, I see the clarity and emotion in their conclusions and in their connections:

“I know she’s strong because it says she was only eight years old when she found out her father was killed.”

Many of them write:

“It is obvious this girl had to make sacrifices because she risked the journey even though she knew there were many women who had been raped on the way.”

Another adds:

“She sacrificed having to leave her grandmother who raised her and was the only person who loved her unconditionally, and who she knew she would probably never see again.”

I can see the realization, the sadness, the seriousness on their faces when they remember that this story is “real.” That it happened to a “real kid” just like them. I breathe a sigh of relief for the first time in weeks and I remind them that they do “get it,” they do “know what to do.” I try to instill a sense of confidence that I know they need and that I hope will bring them success, not just on the Regents.

Time is running out. I’m “closing up” my lesson and I’m left with “thank yous.” I’m not surprised. They’re sweet kids. I often hear, “Thank you, Ms., have a good day.” But this time the thank yous are followed by, “Ya know, that was really cool. I can’t remember the last time I got to read a story in Spanish. We speak Spanish all the time, but we don’t get to read it like this.” The sentiment is echoed as they file out of the classroom. And we’re all smiling. “Have a great day, guys. Be good.”

A former chairperson would always ask me what my “So, what?” was. We’d review lessons and she’d say, “So, what?” It drove me crazy; it took me a long time to get what she meant and now that “So, what?” is ingrained in every lesson I prepare, in everything I do. What’s the takeaway? Why am I doing this? What is truly important? And this time, my “So, what?” is this: they engaged, they connected, they learned, I learned, we laughed, and they left with confidence and perhaps with new feelings of empathy.

I took a chance with a new text and better understand now the value Brave Journeys/Pasos valientes offers to racially and culturally diverse students as they search for meaning in a foreign land. And perhaps, more importantly, the value the text offers to students from racially and culturally homogeneous backgrounds who may lack the understanding and empathy needed to function well in today’s world.